I am Tucker Olson

a family member in a familial ALS family,

a family member of someone we've lost to ALS,

an ALS gene carrier

Indiana

I remember my dad smiling and laughing throughout all of it. He was determined to never let ALS get the best of him.

I am Tucker Olson, and my family history demonstrates the importance of including the pre-symptomatic familial ALS (fALS) population in clinical trials.

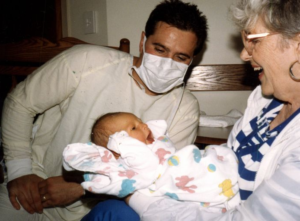

During one’s childhood and teenage years, it is difficult to understand the gravity of a genetic terminal illness. After six years of suffering, my grandmother succumbed to SOD1 familial ALS in 1994, just months before my fourth birthday. I was too young to form memories of the disease’s horrors.

Three generations of SOD1, shortly prior to Olympia’s passing to SOD1 ALS: Olympia Olson, Richard Olson, and Tucker Olson

Richard B. and Olympia Olson

My first memories of ALS are from my early teenage years. My Uncle John was suffering through his battle with fALS. Uncle John shared his love for woodworking with me while his hands were still able. He helped me build a boxcar racer, which I still have to this day in his memory.

Boxcar racer Tucker’s Uncle John helped him build.

I recall my father sharing that Uncle John was accepted into a medical trial shortly after he was diagnosed, and that he had been given a fighting chance at possibly extending his lifespan. Unfortunately, the trial was unsuccessful. He was abruptly pulled from participation. I remember visiting him during his final days in the hospital and saying my goodbyes. By that time, the usage of one finger was his only line of communication to the outer world. ALS trapped him inside his body while his mind remained intact.

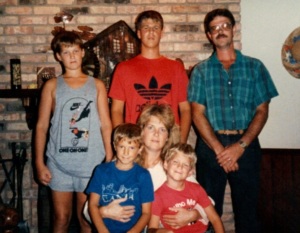

John Olson and his family.

At the time of Uncle John’s passing in 2005, I was 15 years old. Despite being briefly told of the disease’s genetic inheritance pattern for those affected by SOD1 ALS, I thought its impact on my family was in the rearview mirror for the time being. After all, my father was my superhero. I couldn’t imagine him developing the same disease I witnessed whittle away my uncle’s body.

The unfortunate truth revealed itself roughly four years after Uncle John’s death, just a few months after my 17th birthday. My parents sat my sisters and I down at the dinner table. There, they shared the news of my father’s ALS diagnosis. His life expectancy was just three to five years.

In the weeks that followed, my dad spent much of his time on the phone with doctors and researchers. Soon after his diagnosis, my father was accepted into a Phase I clinical trial. We were told that this clinical trial was the first clinical trial designed to target the SOD1 gene, the genetic mutation that was causative of ALS in my father and our family members prior. This trial repurposed an existing medication originally utilized to treat Malaria, called Pyrimethamine, as it was found to reduce SOD1 protein. To us, this meant he had been given a fighting chance. We had hope. During the spring of my junior year in high school, I remember my father and mother traveling from Fort Wayne, IN to Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York for my father’s clinical trial participation. They would make this journey with hopeful spirits eleven times in one year.

As the disease progressed, I remember the countless nights of adjusting my father’s breathing mask so that he didn’t suffocate in his sleep. I remember frantically calling my friends and my neighbors to come help me pick my father up off the ground after his numerous falls. Toward the end, I have memories of cleaning open wounds on my father’s legs from the time spent in his hospital bed and helping him get dressed and undressed. I can recall crying in fear as I frantically attempted to help my father clear his own spit before he choked to death on it. It pained my father to see my fears that I could not disguise.

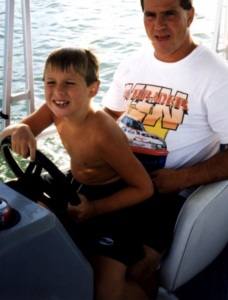

I harbor recollections of trying to maintain a sense of normalcy by continuing family activities. Activities many families take for granted, such as going out to eat. For us, it meant being met with awkward stares from other patrons as a teenaged son helped his disabled father go to the restroom. These are just a few of the daily battles ALS patients and their families experience. Despite it and most importantly, I remember my dad smiling and laughing throughout all of it. He was determined to never let ALS get the best of him.

Rick and Tucker Olson

My father succumbed to ALS in 2013, roughly five years after his diagnosis. To say how long the treatment extended his life, that we do not know for certain. It could have been years, or it could have been months. While “months” may seem short to some, a few months is an eternity to someone with ALS, and an eternity for his children vying for every last moment with the father they adored so dearly. Personally, I firmly believe that the treatment extended my father’s life longer than months. I believe that had the treatment begun in the pre-symptomatic stage of my father’s disease, he could have lived many years longer and potentially could still be with us today. Instead, due to the disease already being clinically apparent by the time it was administered, its effectiveness was equivalent to taking a garden hose to a house already engulfed in flames. In other words, a battle already lost but still worth fighting until the end.

Rick Olson with his brothers and friends at the annual Olson ALS Foundation Golf Outing, Dinner, and Auction

Just four years after my father’s death, his youngest sister Patricia began to develop symptoms of the disease. The first neurologist to evaluate my Aunt Patti did not believe she had ALS. This decision, or lack thereof, would prove costly. After symptoms continued to progress, my Aunt Patti visited with the neurologist that cared for my father. He immediately diagnosed her in the fall of 2017. Due to the disease’s progression and lack of available experimental treatments in clinical trials for SOD1 carriers at the time, my Aunt Patti was not provided a fighting chance. She succumbed to the disease, just ten short months after her diagnosis.

Patricia Rivera-Olson with her son Daniel and daughter Elisa

Just as my Aunt Patti was undergoing the diagnosis process of the disease, I began my own journey of undergoing genetic counseling and testing, SOD1 gene sequencing, to determine whether I had inherited the SOD1 genetic mutation from my father; causative of ALS in my family. Akin to my father’s odds of inheriting the mutation from his mother, the odds of my two sisters and I inheriting the mutation from our father were 50/50 for each of us (autosomal dominant inheritance). In other words, a flip of a coin. Unfortunately, the coin’s fall was not favorable for me. In December 2017, I was provided a genetic sequencing report indicating my inheritance of the SOD1 (L144F / L145F) gene mutation. Years prior, my older sister received the same unfortunate news. This means her children now carry the same risk of inheriting the genetic mutation as my sisters and I did.

Upon learning of my genetic inheritance of the SOD1 mutation, I was told the penetration of the disease is “complete.” In other words, unless I die from something else first, I will develop ALS. I was also told the average age at which the disease becomes clinically apparent is mid-to-late 40s. I stress the words “clinically apparent” as it is widely acknowledged in the neurological medical community that the beginning of the disease process occurs well before it becomes clinically apparent. In other words, people have ALS before it becomes visually obvious that ALS is the correct diagnosis. Despite this, carriers of ALS-causing genes do not have access to pre-symptomatic treatment. Early intervention is key to prolonging the lives of people living with ALS. Recently, Biogen’s Tofersen treatment results indicate that the earlier treatment begins, the greater impact it has on the disease’s progression, quality of life, respiratory function, and muscle strength. Other drug sponsors, the FDA, and the entire ALS community, including researchers and clinicians, need to follow the science and ethics. It is morally imperative to provide a pathway for pre-symptomatic access to treatments. Anything less is cruel and ignores science. Ultimately, we can all do better.